Today’s read is about ~6-8 minutes long.

Hi all,

Welcome to another edition of City Bits. In the 1990’s the city of Bogotá was well known for being the economic and political capital of Colombia, but also for its high levels of pollution and massive traffic/congestion problems. Today we’ll look at how the city built one of the best bus systems in the world, and then kind of screwed up later on. Enjoy!

Today’s focus

The centerpiece of public transit in Bogotá is the TransMilenio, a bus rapid transit system covering ~71 miles (~115km) of roads throughout the city. “Rapid transit” refers to any transportation system that moves on a route that cars, pedestrians or other vehicles can’t access, like a subway. The TransMilenio is just like that, except instead of running on tracks underground, it runs on the road in its own separate lane.

Why it’s great

The TransMilenio is impressive for a number of reasons:

It’s fast: Special bus-only lanes allow for a citywide average bus speed of ~25 mph (~40 km/h). For comparison, buses in Manhattan average just 8.2 mph (13.2 km/h), making TransMilenio buses on average ~3x as fast as their NYC counterparts.

It’s huge: The entire system moves roughly 2.4 million people/day, or roughly 23% of the city’s entire metro population.

On the left, cars sit unmoving in traffic while on the right, TransMilenio buses cruise along in their special corridor. (source)

It’s (relatively) cheap: The TransMilenio cost about 1/10th the originally proposed cost of a Bogotá metro to build, due to bus lane construction generally being cheaper than digging the tunnels or building the elevated tracks needed for a subway/metro system.

It’s efficient: Prior to the TransMilenio system, Bogotá had roughly 20,000 buses in circulation, whereas today that figure is closer to just 3,500. This is a roughly 83% reduction in buses (thus reducing emissions, maintenance costs, driver salaries, etc.) without sacrificing coverage.

It’s accessible (in two ways!): TransMilenio stations are raised platforms built level with the actual bus floor, allowing wheelchairs, strollers, the elderly, etc. to easily board and reduce risk of injury when stepping on/off.

Additionally, separate shuttle buses run adjacent to BRT routes in neighborhoods that are farther away from a TransMilenio stop, picking up passengers for free and taking them to the main stations, improving the system’s reach and accessibility.

It’s eco-friendly and reduces congestion: Roughly 9% of TransMilenio riders are former car owners who now commute via bus. Given Bogotá’s metro population of ~10.7M people, 9% of that equals ~963,000 fewer people driving to work. Even accounting for carpooling, that still means fewer emissions, less gas guzzled, and fewer vehicles in traffic.

It’s safe(r): After installation the areas surrounding TransMilenio stations saw a 79% reduction in collisions, leading to a 75% reduction in injuries and a whopping 92% reduction in traffic-related deaths.

How’d we get here

These stats are impressive, but they become even more so when we understand what the system was like before TransMilenio came along. Back in the 1990s, Bogotá’s bus system was basically the wild west. The city had hundreds of different, decentralized companies operating ~20,000 busses throughout the city. Critically, drivers were paid on a per passenger basis, which meant they were incentivized to pick up as many people as possible… regardless of whether or not they were at a legitimate bus stop. This led to issues like random stops on the curb (slowing down traffic), inconsistent routes and schedules, and in some cases drivers even dangerously racing each other in the streets to pick up more riders.

The lack of centralization or coherent system meant Rolos (residents of Bogotá)1 had little means to lodge complaints, ask questions, and even check schedules/routes.

Peñalosa’s plan

From amidst this chaos comes Enrique Peñalosa, two-time mayor of Bogotá, a legend in the world of urban planning, and a champion of public transit/livable cities.2

Peñalosa first rose to the mayoral office in 1998 and immediately began pushing for the development of a BRT system, not just to curb the aforementioned wild bus driving, but also for all the other benefits listed above. Under his watch, the TransMilenio was finally opened in Dec. 2000, with Peñalosa even shaving his trademark beard for the occasion. Its launch saw many of the rogue bus companies consolidated and centralized, new stations built and old ones refurbished, and more consistent, reliable service implemented throughout the city. At the time, it was hailed as a massive success and inspired similar BRT systems to pop up in additional cities, both in Colombia and around the world.

In my previous update on Amsterdam’s pivot towards cycling, I talked about how public outrage and grassroots efforts shaped their cycling-friendly policy and infrastructure. If Amsterdam is an example of how public opinion can affect policy from the bottom up, Bogotá is an example of how strong-willed politicians can change urban life from the top down, as the TransMilenio's birth and success can largely be attributed to Peñalosa championing it throughout his time in office.

Lack of federal funding nixes metro plans

Bogotá is somewhat of an anomaly amongst global metropolises in that despite its size, wealth, and cosmopolitan nature, it currently does not have a metro or subway at all. While much of this can be attributed to Peñalosa so strongly championing the BRT, another reason is they lacked the federal funding necessary to construct a metro.

This was not for lack of trying. Back in the mid 1990s the Colombian city of Medellín unveiled their new metro system and Bogotá, outraged that their smaller sister city was getting one before them, began clamoring for its own.

However, metros are expensive and Bogotá would rely heavily on funding from the national government if they were to build one. Then, in early 1999 a massive 6.0 earthquake hit the city of Armenia, Colombia causing millions of dollars in damage and killing hundreds. The national Colombian government was forced to divert planned metro funds to earthquake relief instead.3 With no federal funding to build a metro, Peñalosa was able to rally more people to his idea of building the (much cheaper) TransMilenio instead.

Why it (kind of) works (sometimes)

Normally this is the part in the update where I talk about how the city has maintained the success of the system. However, to be honest, while it is still very impressive in many ways, today’s TransMilenio definitely has its fair share of problems:

Despite initially holding a 90% approval rating when first launched, today that number sits closer to just ~20%.

Commuters face cramped conditions, long wait times at stations, and steady reports of theft and sexual assault on buses.

In some cases buses are so crowded people can’t even get off the bus at their stop (see video below).

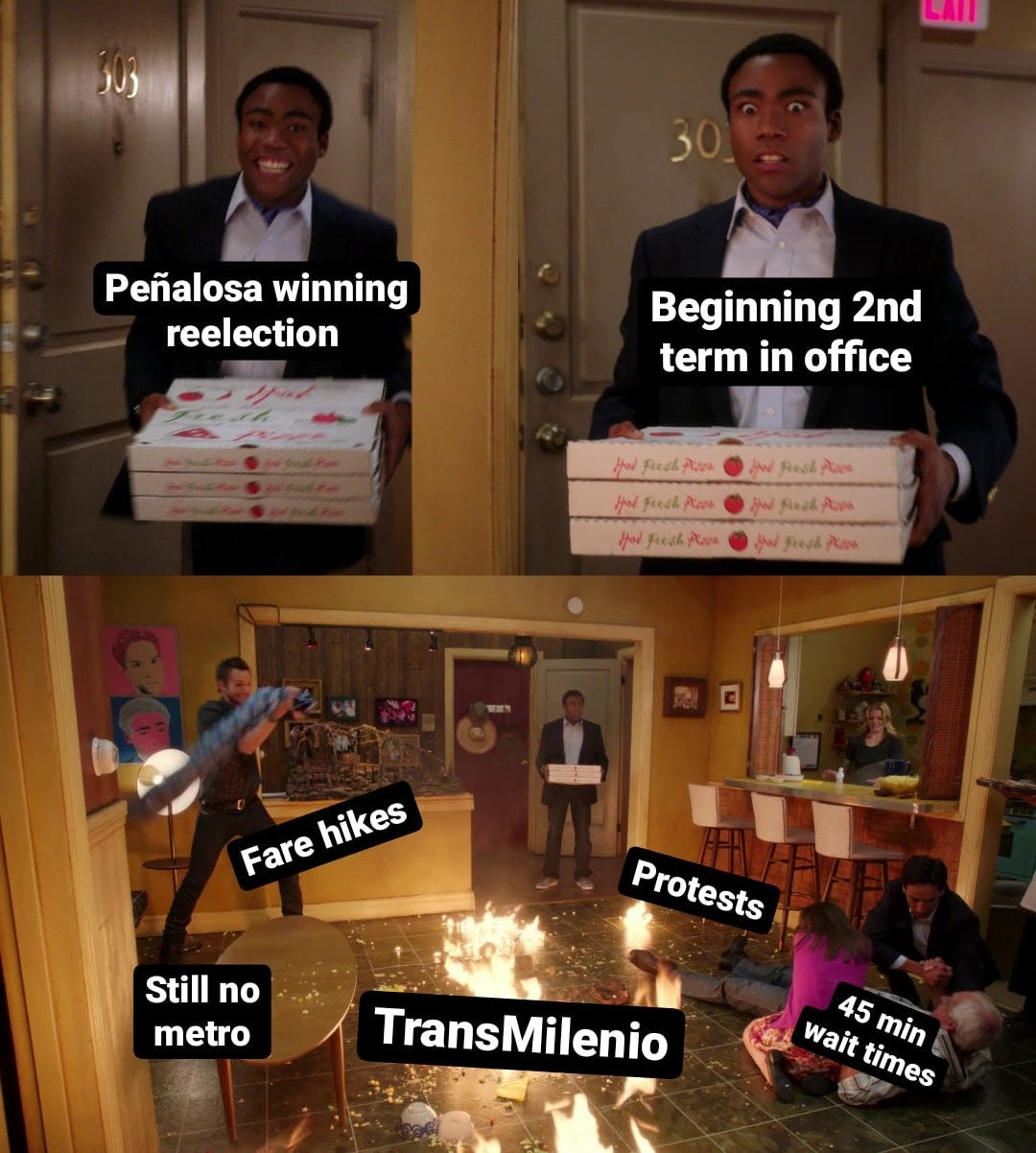

Major protests were staged against TransMilenio practices (mostly fare hikes) in 2006, 2008, 2012, 2014, and 2017. On some occasions these got so bad that riot police were called and entire bus stations were burned to the ground. It’s hard to believe the system that was near universally popular at its inception is now facing this level of public discontent.

So what’s to blame for TransMilenio’s decline? I believe there are three main reasons.

1. Lack of funding and PPP necessitates cost-saving measures

Legally speaking, the TransMilenio is a Public-Private Partnership (PPP), meaning the public sector develops the necessary infrastructure, while the private sector actually operates the system. This, along with the aforementioned lack of federal funding for a metro, means that making revenue was a higher than usual priority compared to other public transit systems.

For example, TransMilenio buses are designed to squeeze as many people as possible onto the buses, ~6 people/sq. meter. In comparison, in Sweden (where transit options are more subsidized) buses are designed for just ~2 people/sq. meter. This is important because it partially dictates how TransMilenio buses are distributed along their routes. Based on this 6 people/sq. meter figure and the expected ridership numbers, comparatively fewer buses are used for each route, meaning they are more likely to be cramped and overcrowded.

2. Lack of follow through, Peñalosa can’t do it alone

Peñalosa devoted much of his first term to his BRT baby, but Bogotá mayors only serve a single 2-year term, so TransMilenio’s growth could not solely rely on him. He was able to add new routes and refurbish old buses in his second term, but keep in mind that his two tenures in office were 16 years apart. That’s a lot of time for the TransMilenio quality to decline, especially since not all subsequent mayors were as supportive of it. For example, extensive fleet repairs were identified as a priority way back in 2011, but large scale refurbishment didn’t actually start until 2019 when Peñalosa was back in office.

The downside of a policy being championed largely by one person is that once they leave office, it’s not always guaranteed that said project will have enough inertia to continue on its own.

3. Lack of complementary transport alternatives, aka “yo bro, metro still a no go?”

The last issue isn’t the TransMilenio’s fault so much as a critique of Bogotá’s public transit as a whole, which is that the TransMilenio can’t do it on its own. The system is being asked to do what, in most other large cities is done through a combination of buses and a subway system. Maybe some folks just love buses (the official term is “bus nut”)4 but for many Rolos riding the TransMilenio, they do so simply because there is no alternative metro/subway option.

Sure, 21 years ago a metro wasn’t possible, but as you can tell from the first half of this sentence, that was over 20 years ago! Plans are underway for a Bogotá metro but unfortunately it won’t be completed until at least 2028. In the meantime the BRT will continue to shoulder a disproportionately large share of the population, and riders will continue to suffer for it.

Barriers to implementation

So what can other cities learn from this? I think there are two major factors that a city wanting to imitate the TransMilenio will need to consider:

Political will

I focused a lot on Peñalosa in this article because he really is largely responsible for much of the TransMilenio’s birth and early success. It takes a tremendous amount of political savvy and effort to push these kinds of massive infrastructure projects through, and similar efforts often fail due to a lack of an equally strong-willed leader/champion.

Public willingness

This might also be because of the second barrier, which is that buses have a public perception problem. There’s ample research that buses are stigmatized, especially in the US, and this means politicians are less likely to support a less popular measure. Some cities just aren’t willing to invest in buses, no matter how many benefits they might bring.

Personally, I enjoy riding the bus, but I also run an entire goddamn newsletter about cities so I acknowledge that I’m probably not the norm. Residents tend to prefer metros over buses, even if stats, costs and other factors might make riding the bus and funding bus service more sensible. Dario Hidalgo, the executive director of the Bogotá-based urban research firm Despacio, notes that:

“Metros are really attractive and no matter if you put the numbers on the table… the general public just dismisses (BRT) by saying all the big cities in the world have a metro. It’s a just a question of image, not reality.” (source)

That preference towards metros and their perceived role as an urban status symbol means that any city wishing to add a similar BRT system will need to ensure the public will even use it in the first place.

Conclusion

Today I was a bit more critical than I have been in previous updates. Regardless, I wouldn’t write about TransMilenio if I didn’t think it was an awesome urban innovation that should be celebrated. We can admire TransMilenio’s initial successes (Peñalosa ended his first term with the highest approval rating of any Bogotá mayor ever), while also recognizing how

too much emphasis on cost-saving measures

a lack of follow-through

and insufficient complementary transportation modes

have greatly diminished the popularity, reliability and general quality of the TransMilenio over the last 15-20 years.

Though the city has been taking measures such as increasing bike lanes,5 walkability, and their planned metro, other cities would be wise to understand the reasons for TransMilenio’s successes while also taking note of how Bogotá could better support the system.

I do want to end on a high note, so I’ll conclude today’s update with my all time favorite urban planning quote from the man Peñalosa himself:

“An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.”- Enrique Peñalosa

I love this quote because I think it speaks not just to Peñalosa’s approach to infrastructure policy, but also his motivations as to why he fought for it so strongly. I’m not really one for getting quotes tattooed on my body, but if I ever did, it’d likely be this one. And it would be on my face.

That’s it for today! As always, thanks for reading and feel free to share it with any public transit nerds you know, and don’t forget to just absolutely BLUDGEON that like button.

-Max

Another term you may have heard is “Bogotános”, but my Colombian friends have told me “Rolos” is more common so I’m gonna side with them. Thanks MB and DG!

I'm not a political journalist, so I mostly focused on his stances towards urban design/public transit. He seems generally decent but please don't come after me if it turns out in 10 years that he was secretly in favor of eugenics or something horrible. To be clear, this newsletter is firmly anti-eugenics.

Armenia is located within Colombia’s famous “Coffee Triangle” and produces much of the country’s coffee export, so relief efforts for one of their most important industries was obviously a priority.

lol