How Rosario, Argentina deals with unemployment and food insecurity

Rosario residents really revere regenerative repurposing of recently revitalized regions

Housekeeping note: These updates normally will come out every other week, but to celebrate Argentina’s victory in the Copa América final, and in a shameless attempt to drive more traffic to my site, I’m releasing this a week early. Future updates will follow the original bi-weekly schedule.

Today’s read is ~5-7 minutes long.

As Argentina celebrates their recent Copa América title, I wanted to talk about another one of the country’s great victories. Today we’ll cover an urban farming initiative in the city of Rosario, which just so happens to be the birthplace of Lionel Messi. Enjoy!

Today’s Focus

Located in the central Argentinian province of Santa Fe, Rosario is a city of ~1.75M people that sits on the mighty Paraná River. There are many interesting things about the city, from their extensive use of Art Deco architecture, to the fact that, in addition to Lionel Messi they are the birthplace of Che Guevara.1 However, today I want to talk about Rosario’s urban agriculture program, the Programa de Agricultura Urbana, or PAU as it’s called. PAU is a multi-faceted government initiative that provides low-income residents with tools and land to start their own urban gardens. Over the last 20 years it has made tremendous strides by combining employment programs, land reclamation projects and the promotion of sustainable agriculture in Rosario.

Why it’s great: “I like that boom boom PAU2”

Originally developed as a way to provide jobs for low-income residents and reduce reliance on imported foods, PAU has evolved into a staple of Rosario’s economic, climate and zoning policy. Its largest impacts are primarily related to

Job creation: ~300 low-income farmers currently participate in the system, 65% of whom are women.

Urban space reclamation: To date ~825 hectares of previously unused space in Rosario has been converted to urban farmland.

Addressing food insecurity: Just two years after implementation PAU was providing fresh, organic produce for up to ~40,000 people in Rosario. Today PAU yields roughly ~2,500 tons of fresh produce a year for Rosario residents.

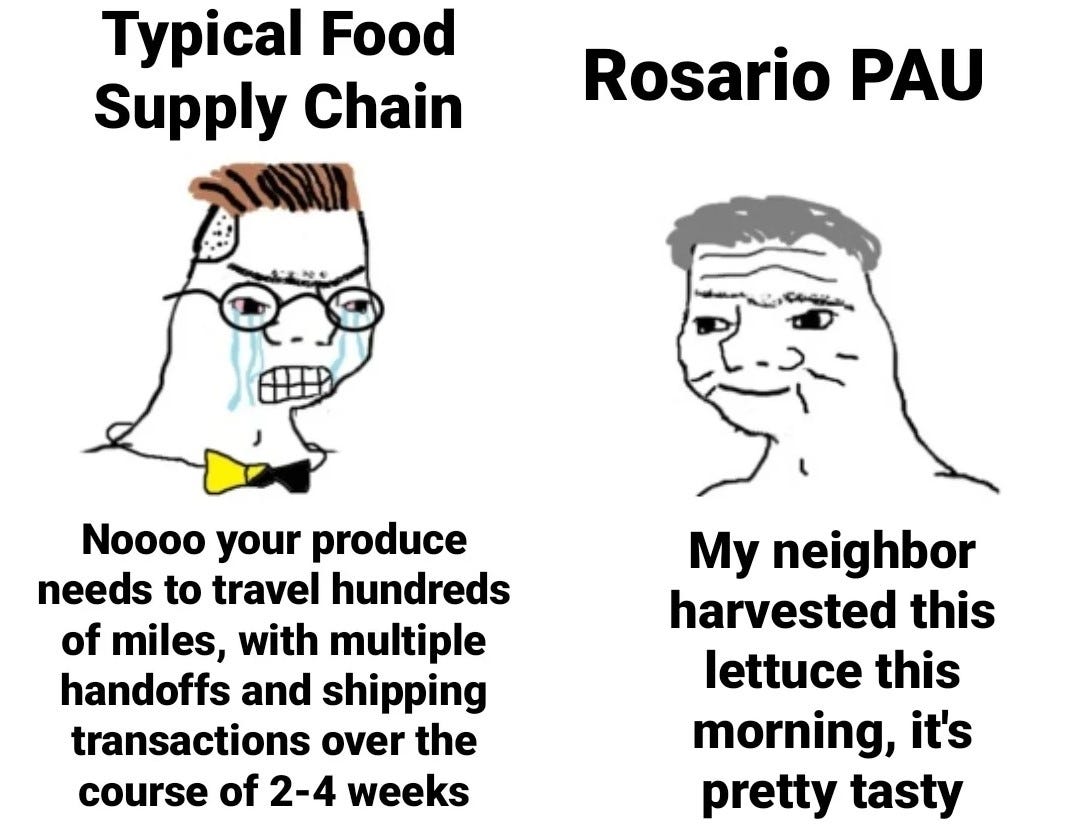

Localization of supply chain: Instead of importing food from hundreds of miles away, residents eat things closer to where they were actually grown. This has numerous benefits such as

Reducing the amount of energy used in transporting goods from farm to table (sustainable supply chain, fewer emissions, etc.).

Reducing food waste, since there’s less time for food to go bad in transit. Consequently food stays fresher for longer after purchasing.

Supporting local farmers and the local economy.

Flood prevention: PAU (along with drainage infrastructure built along the Ludueña stream in the 1980’s) has significantly reduced flood risk by strengthening and revitalizing flood plain areas, since healthy soil absorbs and retains water much better than dry, unused soil.3

How’d we get here

To understand how and why Rosario decided to implement this kind of program, let’s go back to the end of the 20th century, right around the time of PAU’s creation.

Depression

In 1998 Argentina fell into a 4 year economic depression. By 2001 a quarter of Rosario’s residents were unemployed and over 50% were living in poverty. Additionally, failing businesses and unfinished development projects left open, unused lots scattered throughout the city. Rosario’s government was looking for a way to reduce unemployment, and get rid of these unappealing, underutilized plots of land.

Monoculture: Ode to Soy

The other key factor in PAU’s emergence was Rosario’s then overreliance on soybean production. In the early-mid 1970’s, demand for soybeans was on the rise,4 driving farmers in Rosario (and much of Argentina overall) to devote more and more of their arable land to soybean production. This specialization towards a single crop is called “monoculture” which is clearly explained in the table below.

While this can be extremely profitable, the tradeoff is that the area becomes less self-sufficient in terms of meeting its own consumption needs. As a result, Rosario was forced to begin importing a greater percentage of their food because, despite what my ex thinks, not everyone can just eat soy for every meal.5

This issue came to a head in 2001, when the depression had put many farmers out of work, and the city was struggling to produce food locally, forcing them to import at higher and higher costs. Rosario’s foodbanks were constantly depleted, and people were going hungry. These factors pushed the Rosario government to find a way to address unemployment, food insecurity and the underutilization of urban land all at once. Thus, PAU was born.

Why it works: strategies for emPAUerment

Since its initial pilot of 10 farmers, PAU has grown 30x, is now an internationally recognized (and imitated) initiative, and most recently won the WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities grand prize in 2021. So what’s made this program successful? I believe there are three main reasons why PAU has been so impactful and why it has continued to grow in size/scope.

Streamlined, comprehensive government support for participants

The first is, the government of Rosario does an excellent job supporting PAU participants. If you want people to adopt a new habit, you need to make it as easy as possible for them to change their behavior. Had Rosario just told low-income residents to “start gardening more” probably nothing substantial would have come from it. Instead, the government strongly supports PAU participants (PAUticipants?) in 3 main areas:

Finding land to use: PAU maintains a central database that identifies, tracks and distributes plots of land that are suitable for farming, meaning they are nutrient dense/healthy enough to grow crops, and are not going to cause issues with zoning, lack of permits etc. This further streamlines the process of application for citizens.

Providing necessary tools/education: PAU also provides fertilizer, seeds, tools, and educational trainings to help people get started. This way, PAU ensures that citizens can hit the ground running and almost immediately start productive gardens.

Allowing for open markets/sales: The final key step is giving these farmers a place to safely and consistently sell their produce. PAU maintains both temporary and permanent spaces within the city to ensure that participants have a place where they can sell their goods, and in some cases even assists in transporting harvested crops to the marketplace. These spaces also serve as a place for crafts and other artisan goods to be sold, further strengthening the local economy and providing much-needed revenue streams for low-income residents.

So if we think about the individual-level hurdles to starting a garden in a city, they can be boiled down to

Locating a plot of land

Acquiring the necessary tools/supplies/education

Finding a marketplace/opportunities to sell

Rosario supports their citizens at every one of these steps, and that’s a huge reason for the continued growth/success of the program.

Why it works: Broader expansion/education efforts

Outside of directly working with/providing resources for farmers, PAU also ensures its continued growth in two other major ways:

Community education: PAU frequently holds community events that are open to the public, sharing basic strategies for gardening and encouraging residents to start their own gardens at home. Critically, they also approach local schools and hold gardening seminars and awareness days. To date, over 2,400 families and 40 schools have received training on sustainable gardening methods, many of whom later go on to develop their own gardens as well.

Expansion: PAU also does an excellent job in expanding the scope of available land and participants. In 2015 the Proyecto cinturon verde (Green Belt Project) was created to help expand PAU’s reach in the peri-urban (surrounding) areas of Rosario, and in 2013 a PAU offshoot program began offering gardening training specifically for unemployed youths age 20-29.

Why it works: Full integration with city strategic planning and policy

The final key to PAU’s resilience and continued success is their complete integration into the city’s broader planning and policy goals. For example, the city’s strategic plans of 2008 and 2018, as well as their Environmental Plan of 2015 all reference PAU as an important component of Rosario’s future success, especially when it comes to combating the increasingly prevalent dangers of climate change. There is buy-in at all levels and in all relevant departments, ensuring PAU remains a priority in Rosario’s future.

Downsides

Honestly I had a hard time thinking of downsides for this program. It’s relatively low-cost, doesn’t require massive facilities or much technical knowledge to get started, and is a net job creator. Additionally, there are little to no environmental costs because PAU stresses the use of sustainable farming methods (agroecological is the technical term).

You could argue that certain plots of land would be better put to use building housing or providing other services, but much of the land reserved for PAU is chosen specifically because it is not suitable for building, but is for gardening.6 So it’s not like these gardens/parks are inhibiting any other developments.

I think the biggest argument against PAU is that the scale of it is still relatively small. In a city of 1.75M it certainly could be bigger, but while I would love to see this spread to hundreds of more families, this isn’t a true “downside” of PAU so much as an observation of its scale.

Barriers to Implementation

As great as I think it is, if your city wants to start pushing out a similar program, there are a few things to consider:

Climate: Rosario is generally a warm, temperate climate with plenty of rainfall, extremely suitable for these kind of urban agricultural programs. It’s true that certain areas/climates suit different crops, but your range of growable foodstuffs really begins to narrow once a city nears the different climate extremes of hot, cold, dry, etc. It would be much more difficult to replicate this program in an extremely cold city, unless your favorite food is ice soup.

Government support: PAU has thrived in large part because of the high levels of support the Rosario government provides. Similar programs might be able to identify land for farmers, but for example, if they lack the same follow through when it comes to supplying them with tools, education etc. then it will be difficult to replicate PAU’s success.7

Space: When PAU was first implemented, a full 1/3 of Rosario’s lot space was unused/underutilized. You don’t need much space to grow a family garden, but cities with more expensive real estate or a higher utilization rate might struggle finding enough (affordable) land to implement a similar system on a large scale.

Willingness/Agricultural Experience: The last barrier would be participant’s willingness to garden. Many early PAUticipants already had agricultural experience, and while it is relatively easy to train folks to garden (compared to complex engineering jobs), it may still be an issue if citizens don’t feel agriculture is a viable path for them. In today’s day and age you can learn anything online,8 but successful replication of this system would still require people to be okay with farming/gardening as an occupation, or at least a side hustle.

Conclusion

Today we discussed the ways in which urban agriculture programs can address issues like unemployment, underutilization of urban space and food insecurity. We also discussed how, even though Rosario does an excellent job of supporting PAU, a major appeal of urban gardening is that on an individual level it is relatively low cost and easy to pick up. Therefore, even without comparable levels of municipal support it remains a viable option for cities/communities to implement.

Over the last 20 years, what started as a way to get a few citizens working and provide fresh produce has turned into a cornerstone of the city's economic and environmental policy. In a time when some organizations/industries protest that “green” policies will kill jobs, PAU has done the opposite, and found ways to blend job creation and sustainability within the same initiative. While it might not match the scale or budget of larger infrastructure projects that I’ll cover in future updates, PAU is an awesome example of how smaller-scale urban agricultural programs can bring immediate, tangible benefits to a city.

That’s it for today, thanks again for reading and be sure to smash the absolute bejesus out of that like and subscribe button.

-Max

Not as good as Messi at football but probably has his picture hung up in just as many college freshman dorm rooms.

While researching this piece I had to look up the lyrics to this Black Eyed Peas song and I was shocked, SHOCKED, to learn that the phrase “boom boom pow” only appears twice in the whole song. Every other time they just say “boom boom boom”. Did anyone else misremember this? Truly, truly shocked.

You could write a whole paper on this topic but basically there’s a soil metric called “soil porosity” that measures how much void space a given area of soil has, and healthy soil with high porosity can absorb/retain much more water than dry, cracked or “unhealthy” soil.

Largely as a result of huge increases in EU soybean consumption and the US oilseed embargo of 1973.

Veronica if you’re reading this please return my calls you still have some of my DVDs in your car.

For example, if you’re going to build a skyscraper on a patch of land there are many more considerations than if you just want to plant a few heads of lettuce there.

For a really in-depth view of this, you can look at varying levels of support for land reform/redistribution efforts in the Philippines (unsuccessful) vs. in Taiwan and South Korea (extremely successful). Joe Studwell’s book “How Asia Works” covers this extremely in-depth.

I highly recommend Ron Finley (aka The Gangsta Gardener) if you’re interested in urban gardening.

A good way of estimating emissions would be to recreate Rosario in Cities: Skylines

Awesome piece, hoping you get your DVDs back! One small quibble: while efforts such as PAU do inherently reduce GHG emissions from food transportation, industrial-scale ag tends to be so efficient and fertilizer so energy-intensive that the net impact of "eat-local" campaigns can often be a net increase in emissions. Not to say that's necessarily the outcome here, but something to consider as a macro consequence