Superblocks in Barcelona (1/2)

Barcelona's brainstorm bestows bountiful blessings, brilliantly buffs up boring old block blueprint.

This is the first of a two-part series on Barcelona’s superblock concept. You can read the second part here.

Today’s read is 6-8 minutes long.

Hello dear friends,

During the pandemic, cities around the world tried various ways to restore a sense of normalcy. Measures like allowing curbside dining, building new bike lanes, and closing off entire streets to cars not only allowed for socially-distanced interactions, but also increased levels of walkability and showed urban residents how nice low-traffic (or no-traffic!) areas could be. In the past three months I’ve been to Boston, Chicago, and New York, and have lost track of how many times friends have remarked how nice it is to be able to walk safely in the streets without worrying about traffic.

In this sense, the Spanish city of Barcelona is ahead of the curve. While probably better known for their football club, gaudy (or Gaudí) architecture1, and thuper thexy thpanith accent, Barcelona has also been a leader in urban walkability since the early ‘90s. This is perhaps best exemplified by their superblock concept, a unique take on neighborhood design, and the focus of today’s newsletter. In this update I’ll examine what exactly a superblock is, the history of how they came to be, and argue that their success makes a strong case for other cities to consider making their pandemic “adjustments” into more permanent features. Let’s dive in.

Today’s focus: Superblocks

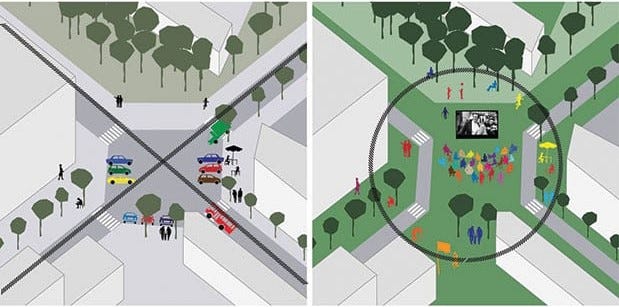

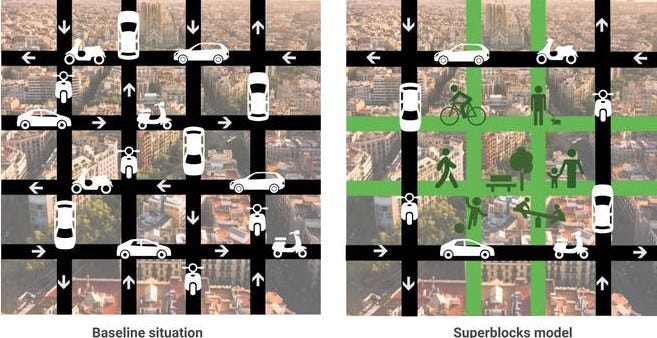

In 2016 Barcelona formally incorporated superilles,2 or “superblocks” into their urban planning vision and began rapidly implementing them throughout the city. A superblock is a 3x3 block area that prioritizes pedestrians, cyclists, and residents over drivers. They do this through a variety of methods such as…

Redirecting most traffic to the perimeter of the superblock

Imposing speed limits on the remaining vehicles that are allowed to enter

Removing parking spaces in favor of bike lanes, benches, trees, etc.

Installing gardens, playgrounds, and public gathering space for residents

Today the number of superblocks has grown 6x since its initial pilot, with plans to build hundreds more by 2030.

Why it’s great

Now that we have a basic idea of what a superblock is, let’s talk about why they should serve as a model to other cities around the world. If you’ve read this newsletter before3, then you know I support reducing (but not totally removing!) cars in cities.4 That’s definitely part of a superblock’s appeal but the benefits go well beyond just reducing traffic. Their core philosophy is that streets should enrich the experience of those living, or even just passing through there. This manifests itself in a number of ways such as:

Prioritizing people over vehicles: Superblocks take space originally intended for cars and transform them into more dynamic, multi-use areas for the community. Streets are narrowed to allow for new bike lanes, traffic calming measures are used to reduce vehicle speeds, and Barcelona’s wide intersections in particular are often converted into central gathering spaces for the block’s residents by installing park benches, urban gardens, and playgrounds.

Increased community interactions: All this new space gives children places to play, neighbors places to meet, and residents safer, slower streets to walk in. Take a look at this video from urbanist Twitter legend Daniel Moser:

The Barcelona 🇪🇸 superblocks are about so much more than traffic calming. Superblocks are about nurturing social cohesion by putting human interactions back at the centre of communities and developing the full potential of streets👇👇

The Barcelona 🇪🇸 superblocks are about so much more than traffic calming. Superblocks are about nurturing social cohesion by putting human interactions back at the centre of communities and developing the full potential of streets👇👇Safe, open spaces beget mixing and mingling, two essential items for community building. Numerous studies show that social interactions with neighbors have benefits such as combating loneliness/depression (especially amongst the elderly), boosting mental health and allowing children the ability to play and explore their neighborhoods.

Safety: Cars are not completely banned from driving within superblocks, but there is a 10km/hr (~6mph) speed limit which greatly reduces the chances of pedestrian deaths or serious injuries. One study found that successful implementation of superblocks throughout Barcelona could result in ~700 fewer premature deaths/year due to the reduced number of collisions, as well as other factors such as fewer emissions and less noise pollution.

Deliveries, essential services, and residents who live within the superblock area can still drive through, though larger vehicles like shipping trucks must go around the 3x3 area.

Noise reduction: Excessive noise levels have been linked to health risks such as dementia in elderly residents and are just generally unpleasant. Before superblocks started popping up in Barcelona, ~57% of the city experienced noise levels over 65 decibels, well above the WHO recommended level of 55 decibels.5 Future superblock implementations are projected to reduce this number from 57% down to just 26.5%, and existing superblocks have already seen reductions to below WHO recommended decibel levels.6

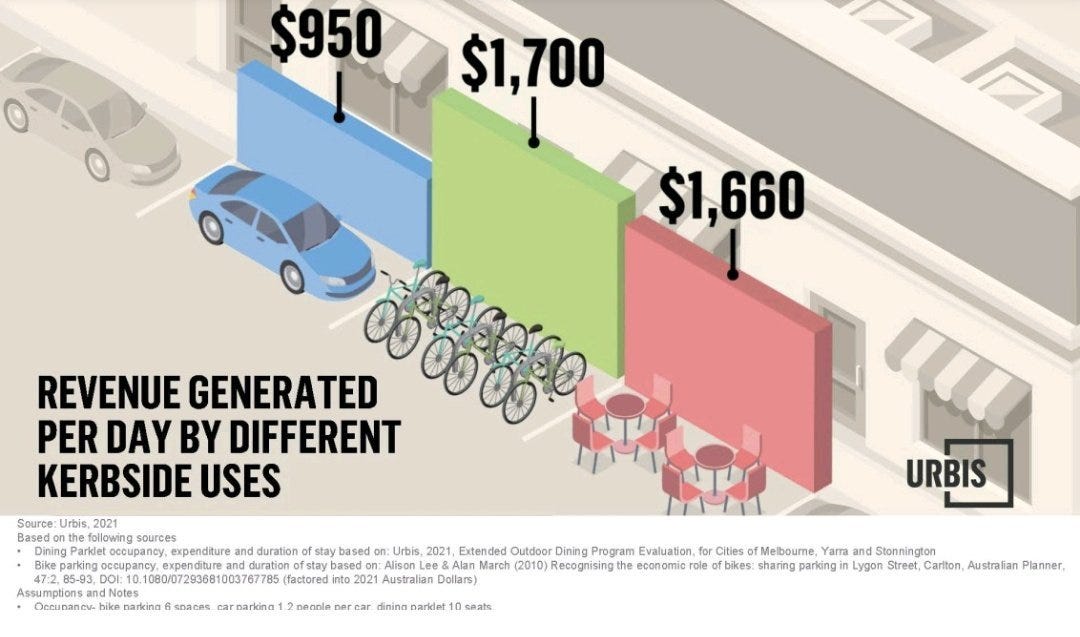

Increased economic activity: One of the biggest arguments against superblocks is that stores and local businesses might suffer due to lowered traffic. Actually, the opposite is true, as local businesses in new superblock areas have seen economic activity rise by up to 30%, and cities around the world like those in Canada or England, have seem similar results after implementing low-traffic initiatives.

This makes sense when we think about how people actually shop. Cars themselves don't buy things, people buy things, and it's generally much easier to stop and check out a store that looks interesting on foot vs. in a car where you may have to first find parking, pay for it, and then finally walk all the way back to where the store is.

Here’s a quick visual on how car parking is actually one of the least profitable uses of curb space for businesses, compared to bicycle parking and outdoor dining.

Equitable: The first superblocks were built in areas predominantly composed of social housing (rent controlled apartments). By selecting areas with subsidized housing, initial superblocks were able to somewhat avoid the gentrification that usually accompanies walkability projects in other cities. It’s worth noting however, that this pattern of placing superblocks in rent-controlled areas will not continue as more and more superblocks are built, simply because subsidized housing is not equally distributed throughout the city. However, if they eventually cover a large enough portion of the city then that won’t matter, as most everyone will have access to the benefits of a superblock neighborhood.

Walkable neighborhoods tend to drive up prices because they are both desirable and scarce, but if they become as widespread as Barcelona plans for them to be, then that becomes much less of an issue.

How’d we get here?

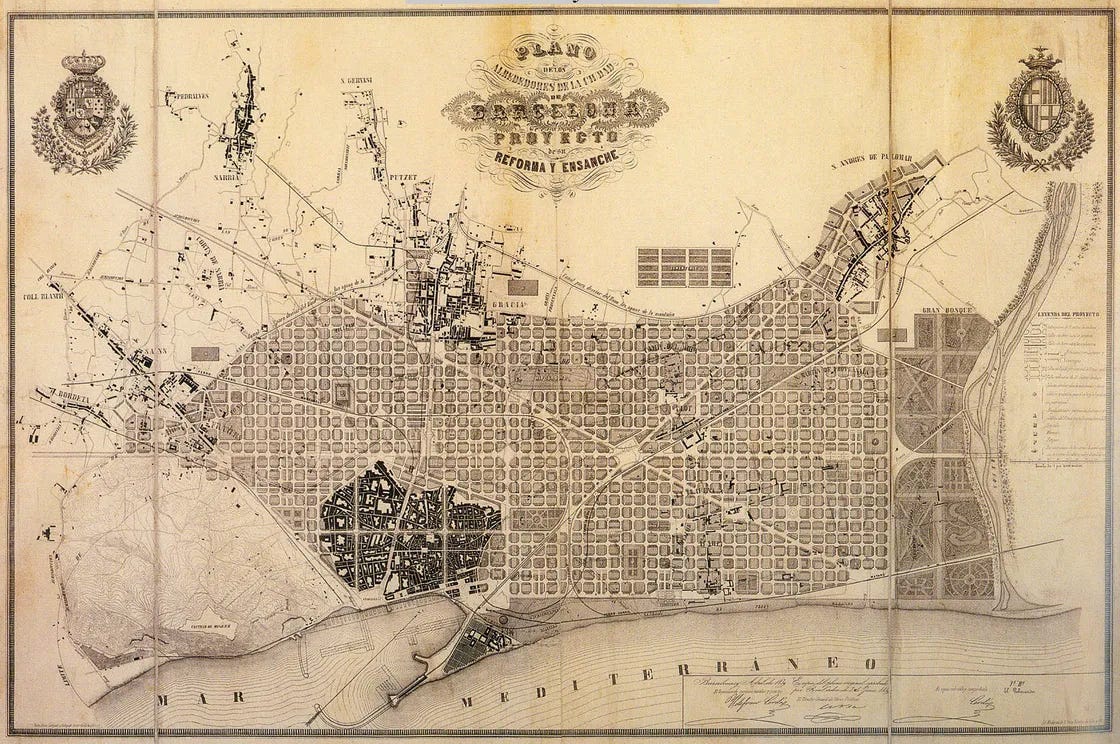

There are a few key characteristics about Barcelona that make it well suited for superblocks. The first is the physical layout of the city itself.

From this aerial viewpoint the city actually looks perfectly designed for the 3x3 block pattern used by modern superblocks. Does this mean when Barcelona was originally built hundreds of years ago they anticipated the superblock plan? The answer is, sort of. Let’s take a quick look at the city’s history to understand why.

Why does Barcelona look like sheet of graph paper?

Modern-day Barcelona’s first formal incarnation can be traced back to the year 15 BC, when it was just a small Roman military encampment called Barcino. Over the next ~1,800 years it would change hands several times, all the while increasing in wealth, influence, and especially population. This growth meant that by the mid-1800’s the city walls that once protected residents now served mainly to pen them in and restrict expansion. Add in a subpar sewage system7 that led to 4 separate epidemics in a ~36 year period, and it was clear that Barcelona could no longer stay confined within the city’s original limits.

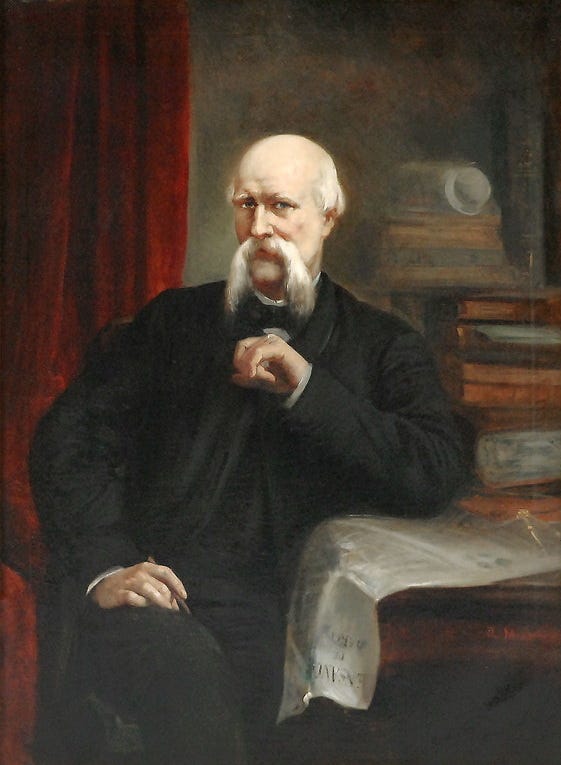

Thankfully, in the mid-19th century the Spanish government finally ordered the walls destroyed, and all of a sudden Barcelona had a golden opportunity to intentionally plan and design their new expansion.8 Luckily for them, the legendary 19th-century urban planner Illdefons Cerdà was up to the challenge.

Even amongst the pantheon of great urban planners throughout history, Cerdà is a pretty big deal, and not just for his facial hair. The man was decades ahead of his time in terms of socially-conscious planning and user-centered design, and is largely credited with inventing the term “urbanization.” Cerdà was especially motivated to solve what he saw as the terrible conditions of the working class, and wanted this new expansion to give each citizen equal access to everything they might need in an urban environment.

His proposal for the “new” Barcelona was to use a grid structure to form mini-enclaves throughout the city that would put all residents within walking distance of public services/resources like clean water, parks/green space, childcare, schools, etc.9 Unfortunately, for various political and economic reasons not all of his plans came to fruition, but his grid layout was, for the most part, successfully implemented. Cerdà’s egalitarian worldview and insistence on such a rigid geometry would go on to form the basis of the modern-day superblock design.10

“You’ll Rueda day you crossed me”

If Cerdà set the stage for superblocks 150 years ago, then Salvador Rueda is the one to thank for actually bringing them to life today.

A passionate civil servant and urban planner, Rueda spent decades in various roles within Barcelona’s government, and saw firsthand how his beloved city was becoming noisier, dirtier, and more congested. Rueda tried numerous ways to combat these trends, such as his experiments with low-traffic programs in the neighborhoods of El Born (1993) and Gràcia (2003-2005). These spiritual predecessors to superblocks featured protected bike lanes, converted intersections, and equally shared roads for pedestrians, cyclists, and cars. Decades before superblocks were formally incorporated into Barcelona’s urban planning vision, Rueda was already tinkering with the idea and making a case for the benefits they could bring.

Despite some initial resistance, these experimental changes were eventually embraced by most residents, and in 2000 he founded Agència d'Ecologia Urbana de Barcelona (the Urban Ecology Agency of Barcelona) to focus more on these kind of urban improvement projects. This agency would go on to serve as the chief design partner for the superblock concept and help spearhead his grand vision.

Don’t just walk here, live here

Like Cerdà before him, Rueda believed in making city life equally comfortable and livable for all residents. For him, superblocks were not just an opportunity to reduce traffic, but to actually make those areas better places to live. In a 2016 interview he notes that:

“We want these public spaces to be areas where one can exercise all citizen rights: exchange, expression and participation, culture and knowledge, the right to leisure.” -Salvador Rueda (source: 2016 interview with The Guardian)

Essentially the urban planning equivalent of “not just surviving, thriving”. This distinction of not just being anti-car, but actually being pro-citizen, is an important concept to understand about Barcelona’s superblocks, and one of the key lessons he learned from his initial pilot programs. Some like-minded initiatives in other cities fall short precisely for this reason: their scope is too narrowly focused on just reducing traffic, rather than actually improving quality of life. Of course the two are related, but many of the most well-received features of superblocks we have discussed today have nothing to do with cars at all, a point that should be carefully understood by any other city attempting to mimic Barcelona’s success in this area.

Conclusion

Today we discussed what exactly a superblock is, and saw the numerous safety, economic, environmental, and quality of life benefits they can bring. We looked at two key figures in Barcelona’s urban history, Cerdà and Rueda, and how despite being separated by over 100 years, their mutual commitment to egalitarian ideals and improving urban life helped create superblocks as we know them today.

We also understood that the superblocks are focused not just on the removal of cars or the reduction of traffic, but actually improving the experience and quality of life for their residents. As cities around the world continue to struggle with how to exist with/after COVID-19, the success of Barcelona’s superblock program should serve as an inspiration for what streets really can be used for. Are they just for transporting people from A to B? Are they for businesses to attract customers? Barcelona’s superblocks have shown us that we can strike a balance between all of these things, and other urban area around the world would be wise to take note.

Of course, city governance is messy, and not everyone is as gung-ho about the superblock concept as I am. Barcelona’s unique qualities also mean that this specific solution might not be as easily implemented in every city around the world. That’s why in the next CityBits update, part two of this series will look at some common arguments against superblocks, some potential downsides, and talk about what kind of areas might be more/less suitable for similar initiatives. If that sounds interesting, or you just want to see more urban planning memes, be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already!

That’s it for today, as always thank you for reading! You can let me know any thoughts/questions you have in the comments below, and if you enjoyed today’s newsletter go ahead and smash the absolute bejesus out of that like button.

Adios,

-Max

ba dum tss

Linguistic fun fact: This is Catalan, not Spanish. Catalonia is the name of the autonomous community in Spain where Barcelona is located, and alongside Spanish, Catalan is one of the two official languages of Barcelona.

Or talked to me after I’ve had more than 1.5 drinks

I won’t rehash all of that here, but you can check out part 1 of my Amsterdam article for a more detailed breakdown of why this is a good thing.

In 2017 Barcelona was the 7th noisiest city in the world.

France also recently began cracking down on excessive vehicular noise, specifically loud motorcyclists and those assholes who remove their mufflers.

To be fair, back then most cities were full of shit, whereas today it’s just New York.

Though the actual official removal of the walls took several years, some residents were reportedly so happy about them coming down that they began hacking at the walls themselves with hammers and crowbars.

You may have seen headlines lately about the “15-minute city” concept, which is basically the same idea.

For any history nerds looking for a more detailed/super in-depth examination of Cerdà and his vision, I recommend this excellent essay here.