This is the second part of a two-part series on Barcelona’s superblocks. You can check out part one here, and if you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe to catch future newsletters!

Today’s update is a ~7-9 minute read.

Hi all,

In part one of this series we learned what Barcelona’s superblocks are, why the city decided to build them, and why they’re great. As a quick refresher, while they do not fully ban vehicles from entering, they do prioritize pedestrians, cyclists, and residents over vehicles, which improves safety and walkability, and also reduces emissions and noise pollution.

They also help build a sense of community by installing gardens, playgrounds, and other public areas, and giving residents the freedom to use it however they want. For example they can:

Hold block parties, picnics, and barbeques

Get a projector, hang a sheet between two lamp posts and have a movie night outdoors

Have everyone dress up in big banana costumes, one person dresses up as a gorilla and then all the bananas team up to beat the shit out of the gorilla

The possibilities are endless.

Today’s update will expand on what qualities Barcelona has that help make superblocks successful there, and why a perceived downside might not actually be that big of a deal. Let’s dive in.

Why it works

There are several characteristics of Barcelona that make it especially well suited for superblocks.

Grid street pattern

The first is the layout of the city itself. Barcelona’s grid structure is incredibly advantageous for planning and implementing superblocks. In order to execute any kind of street reclamation project, a city will have to be able to answer important initial questions, such as:

Planning: How much space are we working with?

Traffic flow: How will we redirect traffic around the superblock? What directions will it flow? Do we need to change two-way streets to one-way or vice versa?

Construction: How wide are the streets? How wide can we make the bike lanes? Do we need to add more sidewalks?

With their standardized grid design, a lot of these questions don’t need to be repeated (or are vastly simplified) with each new superblock. Thus, by cutting down on cost and shortening project timelines, replicating them on a large scale becomes significantly easier. Just take a look at this map of Barcelona, with its neat corners and sensible layout.

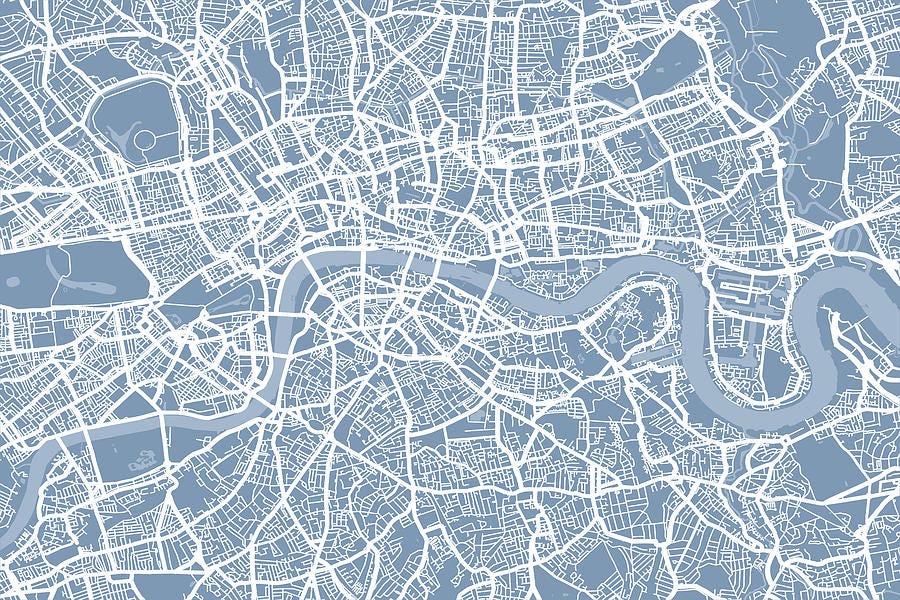

Now for contrast, here’s a map of London, where the streets look like they were designed by a man whose wife left him for a 90 degree angle, and subsequently vowed never to use one again.

It’s certainly possible to have low-car, or car-free areas in London (see examples here and here), but without the same grid structure, all those questions need to be reevaluated for each subsequent build. In Barcelona, however, the grid system dramatically reduces the time, money, and effort spent on the design and construction phases.

Full steam ahead

The second reason superblocks work well in Barcelona is the city’s unusually large intersections, which are often converted to parks, gathering spaces, or gardens, like in this picture below:

Looks kinda big for just a regular residential city street right? Why are Barcelona’s intersections so large? Is it an architectural choice, or maybe something to do with drainage? Do Spanish drivers just love Tokyo-drifting through intersections?1

The answer is, back in the 19th century when Ildefons Cerdà was planning his expansion of the city, he believed that a key part of future urban travel would be … electric steam trains.2 So he designed the intersections to accommodate the much larger turning radius of those vehicles. Now, much to the dismay of steampunk weebs and Elon Musk, this technology never really caught on, but the larger area does make an excellent spot for building the superblock’s parks, gardens, etc.

Density

The next beneficial characteristic of the city is its relatively high density. While superblocks are a generally low-tech, low-cost initiative, they still rely on a minimum level of density to justify the investment and maximize quality of life ROI. Barcelona isn’t topping any global urban density lists, but it’s good enough to justify superblocks in most neighborhoods throughout the city.

Transportation alternatives

Superblocks also work well in Barcelona because it has a strong selection of transportation alternatives. These include:

Bike paths and sidewalks that are well-maintained and accessible (both inside and outside of superblocks)

A comprehensive bikeshare program (named Bicing) that has been expanding throughout the city since 2007

Micromobility options like Lime, Bird, Bolt, and others that have been granted licenses to operate within the city

An extensive subway system, with an aboveground tram network that helps fill in the coverage gaps

A revamped bus network thanks to Salvador Rueda, who I talked about in part one of this series, and who also happens to be the chief architect of the superblock concept. That Rueda had a hand in improving transit networks and also championed a major initiative to discourage driving is no coincidence. Like we saw in Bogotá with Mayor Peñalosa’s multiple terms, leadership continuity significantly helps ensure the long-term success of urban initiatives.

This parallel growth of superblocks (which makes driving harder) and transportation alternatives (which makes not driving easier) is a theme we’ve seen in other cities. It feels like I say this in almost every newsletter now, but if you want people to drive less, you’ve got to make it as easy as possible for them to do so, and Barcelona’s wide array of transit alternatives is definitely a step in the right direction.

Ask for forgiveness, not permission.

The final point I’ll make about why superblocks have been successful in Barcelona is less about the physical characteristics of the city itself, and more about how the city introduced them to residents.

It’s a common complaint of many city residents (and city planners) that a lot of urban projects sound promising, but are slowed down by legal or political hurdles. Town halls must be held, environmental assessments must be made, residents must be informed, and suddenly the five-year timeline is taking eight years and costs $50 million more than expected.

Then deputy mayor of Barcelona Janet Sanz Cid understood this, and so for the first (official) superblock pilot, Barcelona basically just … skipped all that. In a relatively short amount of time, a superblock pilot was built in the El Poblenou neighborhood without much fanfare, or input from locals at all. Aside from a few flyers, most residents simply woke up to find they now lived in a superblock.

To some, this might seem shocking, or even tyrannical. And while there was some initial resistance, people eventually came around and embraced the idea. It’s like when you accidentally order the wrong thing at a restaurant but find out you like it, or when Harry Styles left One Direction but then released Watermelon Sugar. Eventually people get over it and find they’re happy with the changes.

This gambit proved to be a valuable moment for the city because in response to the initial shock and reactionary pushback, the Barcelona government offered to hold proper meetings in which they gathered feedback and input from the affected residents. Then, a few weeks after installing their pop-up superblock, the city updated some of their designs and installations based on what the neighborhood in Poblenou actually wanted. In the end, residents felt more included, and the city got their first superblock built in record time.

As the man himself, Salvador Rueda, put it:

“Now we know that the main problem is the resistance to change that occurs at the beginning of the implementation of the superblocks.”

And once other Barcelona residents saw the benefits for themselves, future implementations became easier from a publicity, marketing, and education standpoint. This urban planning equivalent of asking for forgiveness, not permission isn’t a strategy I’d always recommend, but by and large it worked for Barcelona.3

Arguments against superblocks

Now that I’ve spent the past ~1.5 updates talking about how great superblocks are, let’s take a look at some of the arguments against them. One of the main concerns from opponents of superblocks is the fear that restricting vehicular travel through the center of the superblock would worsen traffic around its perimeter. It’s a fair question, and luckily we have some data on this.

In the Poblenou pilot, traffic around the perimeter of the superblock did increase … by just 2 to 3%. Meanwhile the amount of vehicle traffic within the superblocks decreased by 58% (remember, superblocks limit, but don’t totally ban vehicles from entering).

How can this be? If there’s a decrease in traffic within an area, wouldn’t we expect to see a roughly equal increase in traffic around the perimeter? Well, not necessarily. This next part requires a little bit of traffic engineering theory so put on your thinking caps and let’s take a look at why.

Reduced demand

So the question is: If you decrease the space available for driving, does this increase traffic in the other remaining areas?

There’s a few things to consider here:

Firstly, it’s important to understand what “traffic” really is. It is not some static, monolithic entity that just randomly comes and goes. It’s the cumulative result of thousands of individuals making decisions about where, when, and how to drive (or not drive), combined with external factors like construction, accidents, natural disasters, etc.

Secondly, we need to understand how traffic moves. Even though we use language like “the flow of traffic” or “a stream of cars,” traffic doesn’t really behave like a liquid, which occupies a space with a fixed volume. A more accurate analogy would be that traffic is like a gas, which expands or contracts to take the shape of its container. In this case, that container is the amount of road space available for driving.

An easy demonstration of the variable volume and speed of traffic is rush hour, when you not only have more cars on the road, but they also move slower.

So what does this have to do with superblocks? Well, if traffic occurs because of individual decisions, and it reacts based on the space available to it, then the right policies or engineering decisions can actually influence the total number of people who are driving overall. If folks expect driving to be more of a hassle, for example due to reduced space (like in a superblock), then they might just choose to drive less. And this is a well-documented phenomenon:

In 2011 a section of Los Angeles’ I-405 freeway needed repairs/improvements and was scheduled for temporary closure. Local media began warning residents of the impending “Carmageddon,” prophesying hour-long traffic jams and complete gridlock. In reality, the California Department of Transportation reported fewer cars on the road, and remaining traffic actually moved faster than normal, even with the road closure. Additionally, local Metro ridership went up 50% for that weekend.

In 1973 a section of New York City’s Westside Highway suddenly collapsed, cutting off access for the ~80,000 cars that used the highway each day. Rather than causing traffic jams on the remaining roads, roughly half of the total traffic volume simply disappeared, and the remaining traffic was assimilated into the surrounding roads without incident or noticeable increases in travel time.4

So based on what we just discussed, we would expect that by taking away space for cars, widening sidewalks, installing bike lanes, and improving public transit, we would see a decrease in the amount of cars on the road, and an increase in the amount of trips taken by bicycle or on foot. And that’s basically what did happen:

In Poblenou there was a 58% decrease in traffic within the superblock with just a 2-3% increase around the perimeter

In the Gràcia neighborhood, after installing a superblock they found car traffic dropped 15% from ~96,000 to ~82,000 trips annually. This coincided with a 10% increase in foot traffic, and a whopping 30% annual increase in the number of total cycling trips

And in the Sant Antoni barrio, a superblock led to an 80% decrease in overall traffic, along with a 5 decibel drop in noise levels and a 33% reduction in NO2 pollution

The lesson here is, if you make driving less convenient (and also make public transit, walking, and cycling easier), people don’t just blindly continue driving, they tend to reevaluate their choices. That’s why reducing space for driving doesn’t necessarily worsen traffic, since it might disincentivize people from driving at all. In fact, Rueda’s models estimate that if the superblock plan is implemented to completion, it will result in a massive 21% overall decrease in car volume throughout the city.

Do they just hate cars?

In many cities, there’s a kneejerk reaction to reducing parking spaces or narrowing lanes that goes something like, “I like driving, or I need to drive, and I feel like I’m being penalized for it." I think a more realistic, and frankly fair, way to think about it is to consider that by driving, you are actually already penalizing everyone else with pollution, noise, taking up space, increasing the potential for serious car accidents, and so on. If moves toward equality feel unfair, it might just mean that the current state is already unfair in your favor.

And this was certainly the case in Barcelona. Prior to the start of superblock construction in 2016, 70% of Barcelona was devoted to cars in the form of roads, parking spaces, parking garages, etc. — despite only 20% of residents owning one. With that in mind, superblocks seem like less of an attack against cars, and more of a leveling of the playing field for everyone else.

I am not for getting rid of cars entirely. Some people really do need to drive and that’s fine. But I do believe that through good policy, such as improving transportation alternatives, the number of people who “need” to drive can (and should) be reduced in most major cities.

Lastly, while reduced demand is a desirable, and likely result of building more superblocks, it is admittedly harder to model the impact of multiple superblocks together. Maybe traffic increases 2-3% when you have just one, but if you build four or five superblocks in a row, does that compound the effect? The best estimates point to a 13% reduction in the amount of people driving as the point where, even with additional superblock construction, traffic intensity and congestion will not worsen. Models released by the Barcelona government estimate a 21% reduction in traffic, which is obviously above that 13% threshold, but I’ll be closely following this over the next few years to see how it actually plays out.

Conclusion

Well before the pandemic forced cities to scramble for open-air spaces and greater walkability, Barcelona’s superblocks were bringing these benefits to their residents. And while this concept is not unique to Barcelona, its formal inclusion into the city’s strategic vision and the sheer scale of their planned efforts make the city an inspiration for creating more walkable, more livable urban spaces.

And they aren’t just relying on superblocks alone. The city is constantly promoting other methods to boost public transit use and normalize the idea of people, not cars, being the most important part of a city. For example:

Locally organized “bike buses” gather hundreds of neighborhood children to bike to school safely and encourage cycling

T-Verda public transit passes offer 3 years of free rides to any citizen who turns in an older (i.e. less environmentally friendly) vehicle

Car-free days allow people to roam the streets freely and demonstrate the possibilities of reduced car neighborhoods

In most places, a street is just for driving and parking. In Barcelona, it can be anything you want — and as the pandemic continues to shape how we imagine what urban space should be, Barcelona’s superblocks are a positive, tangible example of what it could be.

That’s it for today, thanks for reading another edition of CityBits! Special thanks to RH for their impeccable editing abilities as well. If you enjoyed this article and want to help me out, you can share it with a friend who likes urban planning/memes or just demolish that like button and give me some more internet clout.

Until next time,

-Max

In Spain they actually called it Sevilla Sliding, or Valencia Vroom-vrooming, but that’s not important for today.

So he was way off with this one but hey, Barry Bonds didn’t always hit homeruns either.

This certainly isn’t the first instance of cities plowing ahead and implementing solutions with little to no advance warning, bike lanes in particular are often built out overnight with nothing more than a can or paint or a few traffic cones, as we’ve seen with Amsterdam in the 1970s and ‘80s, and in NYC during Janette Sadik-Kahn’s tenure as DOT Commissioner.

The opening chapters of Sam Schwartz’s “Street Smart: the rise of cities and the fall of cars” has an excellent, more detailed accounting of this for anyone more interested.

Interesting article. I live in Barcelona and I'd say there are a few more reasons why they work well. One is to do with the values and norms of many people living in Catalonia and Spain, and another would be that the superblocks are not that different from the Ramblas that pretty much each neighbourhood has (or a version of it), a wide largely pedestrian or at least a sectioned-off pedestrian strip in the middle where bars can put out their tables and chairs, there are benches to sit on, are generally tree-lined, and people walk their dogs, etc. Carrer Meridiana, Rambla de Hospitalet, Rambla de Poblenou, Passeig de Sant Joan, and of course the famous Rambla de Catalunya, etc. There are also many pedestrianised streets -- most of Gracia is for pedestrians, Gran via de Catalanes and Diagonal are being made into one long Rambla, and so on. Plazas are also quite common in all neighbourhoods so the idea of making spaces for people to just interact and relax, is not revolutionary. Superillas are cool, but they're an addition to what already exists.